Greetings from Juergen

Greetings from Juergen

Hi all,

This week's stories all share something unsettling: the most important action isn't what gets shown—it's what gets pulled, banned, or never admitted in the first place. Amy Sherald withdrew her entire retrospective from the National Portrait Gallery rather than let curators remove a single painting of a trans model reimagining the Statue of Liberty. San Diego Comic-Con reversed course and banned all AI art after artists organized and pushed back hard enough that the convention needed a new policy in 24 hours. J.Crew's latest campaign turned out to be AI-generated, but you only found out after devoted fans spotted the warped feet and morphing jawlines—the synthetic origins were deliberately withheld until someone called it out.

Meanwhile, young Greenlanders responded to Trump's annexation threats with TikTok videos imitating the "fentanyl fold"—that distinctly American posture of extreme opioid sedation—turning what the U.S. already circulates so widely into a weapon of satire. Even Trevor Paglen's exhibition at Jessica Silverman traces how the things we're not supposed to see have shifted: during the War on Terror, people didn't want images circulating; now they're taking selfies at military bases. When withdrawal, refusal, and concealment become the headline, we're not just tracking what art gets made—we're watching a shadow history being written in negative space.

Data Driven Art

Weaving the Digital: African Artists at the Intersection of Textiles, Craft, and Technology

A fascinating piece from African Digital Art profiles artists who are transforming traditional weaving practices through digital technology—from Diane Cescutti's Nosukaay, an interactive loom installation that earned Prix Ars Electronica recognition, to Bubu Ogisi's I.AM.ISIGO Digital Mystery System, which archives endangered weaving techniques through interactive platforms.

What excites me about this work is how it reframes the conversation entirely. Weaving in the African diaspora was never just decorative—it has always been a code, an archive, and a survival technology. When projects like Nosukaay or Woven in Wa plug looms into sensors and algorithms, they're not "adding tech" to craft. They're revealing the computational logic that was already there.

Pattern becomes data, gesture becomes narrative, and ancestral memory can literally light up, update, and answer back in real time—in a way Western fashion and textile culture can rarely claim for itself.

How long until we stop seeing these projects as "craft meets technology" and start recognizing them as technology finally catching up to craft?

AI in Visual Arts

Fashion Photography's AI Reckoning

When J.Crew's latest campaign was exposed as AI-generated—complete with morphing jawlines and warped feet—devoted fans of the brand's Ivy League aesthetic felt betrayed. Max Lakin's essay in Aperture explores how fashion photography is grappling with AI's rise, from brands like Guess and J.Crew turning to synthetic imagery to the photographer Charlie Engman, who's been exploring AI's creative possibilities while watching entry-level jobs vanish.

This story hits close to home because I've lived through this disruption before. When I moved to New York in the mid-80s to become a photographer, I chose special effects photography over fashion—working with massive 11 by 14 view cameras, creating up to 170 exposures on a single piece of film for clients like Henry Rees. We'd figure out how to get babies into pill bottles without Photoshop, without AI, through pure photographic craft. Then digital technology came along and made those skills obsolete. I had to reinvent myself as a programmer, spending years in corporate America before returning to art. Now I'm using AI in my own work, but I understand the vertigo that fashion photographers must feel watching their industry face the same reckoning I experienced decades ago.

What's fascinating is that Charlie Engman, mentioned in this piece, produces genuinely thoughtful AI work that passes my "not AI slop" smell test—yet even he's seeing brands realize they don't actually need AI when CGI is cheaper and more controllable.

Is the race to replace human creativity really about innovation, or just another way to optimize costs at the expense of craft?

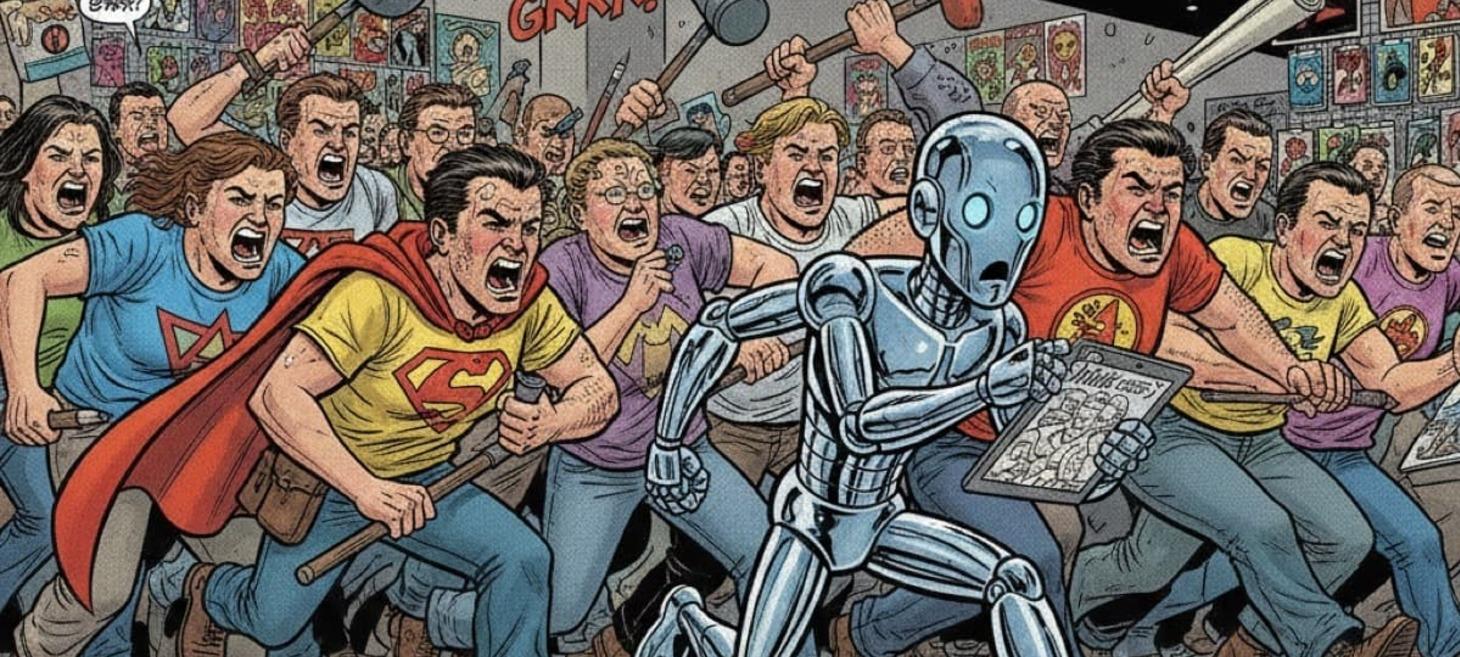

San Diego Comic-Con Bans AI Art After Artist Pushback

San Diego Comic-Con just proved that artists still have power when they organize. After backlash from concept artists and illustrators, the convention reversed its AI-friendly policy in less than 24 hours, reports 404 Media via Boing Boing. The new rule is absolute: no AI art in the show, period—not even if labeled or non-commercial. The old policy had been quietly in place since 2024.

You might not think of San Diego Comic-Con as the art institution most likely to push back against the advance of AI, but here we are. I wonder whether all of it is artist pushback or if some of it is reader pushback as well.

The employment impact is real and happening now. Marvel used AI for "Secret Invasion" title sequences. Coca-Cola ran AI-generated commercials. Studios increasingly use generative AI for storyboarding and design work, rather than hiring artists. At Dragon Con, a vendor was escorted out by police for selling AI art.

What does it say about the moment we're in when convention organizers need police to enforce authenticity?

From Secret Bases to AI Skies: Trevor Paglen and the Techno-Sublime at Jessica Silverman

Trevor Paglen has spent two decades photographing what we're not supposed to see—secret military bases, drone surveillance systems, unidentified objects in orbit—and now his exhibition at Jessica Silverman traces how seeing itself has evolved. In a sprawling conversation with Katy Donoghue for Whitewall, Paglen reveals that the architectures of secrecy he documented during the War on Terror have returned, just with different visual politics: "Back then, people didn't want images circulating. Now you've got people taking selfies at military bases."

What I love about Paglen’s “techno sublime” is that the real subject isn’t the satellite, the drone, or the AI sky at all—it’s the blind spot. These hazy horizons and glitchy cloudscapes turn secrecy itself into material, asking us to sit with everything we can feel is there but can’t quite name: surveillance networks, invisible infrastructures, algorithms scanning the sky and our faces alike.

In a culture obsessed with resolution and explainability, this work quietly insists that the most honest images of our era might be the ones that admit they cannot fully show us what’s going on.

His current research ventures into neuroscience and magic—exploring images not as representations but as stimuli that produce neural patterns, acts of conjuring that materialize from prompts—which feels uncomfortably relevant to our AI moment.

Design

What Is Human-Centric Design, and Why Does IT Matter?

Human-centered design sounds like the kind of thing everyone agrees with in meetings before quietly going back to optimizing conversion funnels. Faisal Hoque's piece in Fast Company makes the case that in our AI-accelerated world, designing for actual humans isn't just noble—it's the most practical path to creating value, bridging customer experience with employee satisfaction.

I spent years heading UX at a financial institution in the 2000s, so I've seen this movie before. What strikes me now is how human-centric design has become a kind of experience greenwashing. Companies drape themselves in Donald Norman's baseline principles while using dark patterns and data to extract every last drop of value. It's not just a distraction from profit-maximization—it's laundering extractive intent in the soothing language of empathy and care.

When organizations trumpet human-centered values while their systems relentlessly squeeze both employees and customers, we're not witnessing a failure of execution. We're watching a deliberate disconnect between what's said and what's designed.

Are we designing for humans, or just getting better at making extraction feel humane?

Art and Politics

Not so Sublime: What the Cancellation of Sherald's Retrospective Reveals About Curatorial Autonomy

Amy Sherald's cancelled retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery is making headlines—not for what was shown, but for what wasn't. Rebecca Bennett's detailed analysis for the Center for Art Law walks through how Sherald pulled her American Sublime exhibition after curators considered removing Trans Forming Liberty, her ten-foot portrait reimagining the Statue of Liberty as trans model Arewà Basit, amid broader administrative pressure on the Smithsonian.

What jumps out to me is that this reads less like a one-off culture-war dustup and more like a stress test for who actually holds intent in our big public art institutions. If museums are quietly rewriting shows to preempt political blowback, we're no longer just arguing about taste—we're watching the storytelling power of a "national archive" drift from curators and artists toward whoever holds the purse strings.

That's exactly why those boring-sounding internal censorship policies suddenly matter—they're one of the few tools left for drawing a bright line between genuine curatorial judgment and the kind of self-sanitizing that erodes public trust long before any official ban ever hits the headlines.

When independence becomes this conditional, who gets to decide what counts as America's visual history?

Greenland Makes Fun of 'American Culture' by Pretending to Be Fentanyl Addicts on Tiktok

When Donald Trump threatened to annex Greenland, young Greenlanders responded with the most cutting weapon they had: TikTok satire. Videos tagged "Bringing American Culture to Greenland" show residents imitating the "fentanyl fold"—that heartbreaking posture of extreme sedation that's become visual shorthand for America's opioid crisis. IBTimes UK reports that while some see this as biting political commentary, others argue it trivializes addiction. The irony? Greenland has virtually no fentanyl problem, making this purely a cultural export critique.

This is performance art with teeth. What I find fascinating is how these creators turned America's most visible public health failure into a mirror—one that reflects not drug addiction itself, but our tendency to export crisis as culture. The U.S. packages its disasters alongside its media, its military presence, its political swagger.

The videos aren't mocking addicts; they're satirizing American moral authority. When you threaten to annex someone's homeland, don't be surprised when they hold up your ugliest contradictions for the world to see.

Is this where digital protest lives now—in the viral weaponization of a nation's own imagery?

Future Trends in Art and Tech

Mega-Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist Shares His Predictions for Art in 2026

Hans Ulrich Obrist—the Serpentine Galleries' artistic director often credited with redefining what curators do—has shared his predictions for art in 2026 with Maxwell Rabb at Artsy. What caught his attention in 2025 wasn't another blue-chip auction record or viral AI artwork, but something more fundamental: exhibitions that actually made strangers talk to each other.

I find myself torn about the expanding role of curators as "cultural connectors." Sure, that sounds great in theory—but curators are also gatekeepers who decide which artists and ideas get amplified and which don't. That concentration of influence has always made me a bit uneasy, even when I respect the person wielding it.

Still, when someone like Obrist makes predictions, I pay attention. His three forecasts for 2026 feel grounded in what's actually happening: artists using AI as a coordination tool rather than just an image generator, long-duration projects that resist exhibition calendar compression, and biennales rejecting carbon-heavy spectacle for local production and free admission.

What strikes me most is his emphasis on "togetherness in a polarized world"—can art really create spaces where people who'd never otherwise meet actually connect, or is that wishful thinking?