Greetings from Juergen

Greetings from Juergen

Hi all,

This week's stories focus on a question: when we try to measure art's value—through cortisol drops, depression metrics, or AI-powered engagement scores—are we actually understanding it better, or just reducing it to what fits on a spreadsheet? A fascinating UCL study claims viewing original artwork drops cortisol by 22% compared to just 8% for reproductions, but I can't help wondering if that's really about the art itself or simply the experience of leaving home and walking through museum spaces. Meanwhile, Douglas McLennan argues museums should build conversational AI "Digital Twins" to personalize interpretation at scale, which sounds promising until you remember my wife and I already do this with Perplexity because wall labels tell us so little.

Elsewhere, six U.S. cities are finally transforming streets into permanent pedestrian zones, creating blank canvases for public art if we don't let them become well-designed but culturally empty spaces. Brian Dettmer carves obsolete encyclopedias into sculptures that expose the beautiful guts of outdated information technology. A retrospective of 25 years of design reminds us that the moments that change everything rarely feel safe when they first appear. And the debate over whether Norman Rockwell was patriot or antifa shows how quickly cultural symbols get weaponized when everyone's trying to claim the same nostalgic territory.

If we keep routing art through scientific and metric lenses, measuring its impact in data points and engagement stats, will that deepen our respect for creative work—or quietly narrow what counts as a worthwhile experience?

Public Art

These 6 US Streets Will Become Scenic Pedestrian Zones in 2026

American cities are finally catching up to their European counterparts. As Elissaveta M. Brandon reports for Fast Company, six U.S. cities—from Houston to San Francisco—are permanently transforming streets into pedestrian zones in 2026. These aren't weekend experiments or seasonal closures. They're permanent reimaginings of public space, turning former roadways into promenades, plazas, and parks.

What excites me most about this shift isn't just the urban planning victory—it's the opportunity for public art. These pedestrian zones are blank canvases waiting for creative intervention. Art doesn't just decorate these spaces; it gives them identity and makes them destinations worth visiting.

The synergy here is obvious but often overlooked: pedestrian spaces create the conditions for experiencing art the way it's meant to be experienced—slowly, from multiple angles, without the distraction of traffic or the rush to the next block. You can't appreciate a sculpture or mural from a car window at 30 mph.

Will these new pedestrian zones become platforms for bold public art, or will they remain well-designed but culturally empty spaces?

Who Owns Public Space? Three Active Models of Shared Management Shaping Urban Commons in Europe and New York

Three models for managing public spaces—from sponsoring historic benches in Paris gardens to building collaborative play areas in Bronx housing projects—are showing fresh approaches to who gets to care for and shape shared urban environments. Antonia Piñeiro's piece in ArchDaily walks through initiatives like Paris's Adoptez un banc sponsorship program, the Main Verte community garden framework, and New York's The Common Corner project at Morris Houses.

For me, this resonates because of work I've done with non-profits supporting muralists. Too much of an artist's time working in public spaces gets eaten up by permissioning battles and bureaucratic red tape that makes displaying public art unnecessarily hard. These models matter because they show different pathways through institutional gatekeeping—whether it's sponsorship, self-management by citizen groups, or collaborative design processes.

What I find interesting about these approaches is they're not just about physical infrastructure. They're essentially testing governance models for creative expression in public domains. If we can establish frameworks for managing benches and gardens through distributed responsibility, why not public murals or street art?

Could these participatory management structures finally give artists clearer paths to bring their work into public view?

Societal Impact of Art and Tech

Engaging with Art Is Good for Your Health, New Analysis Reveals.

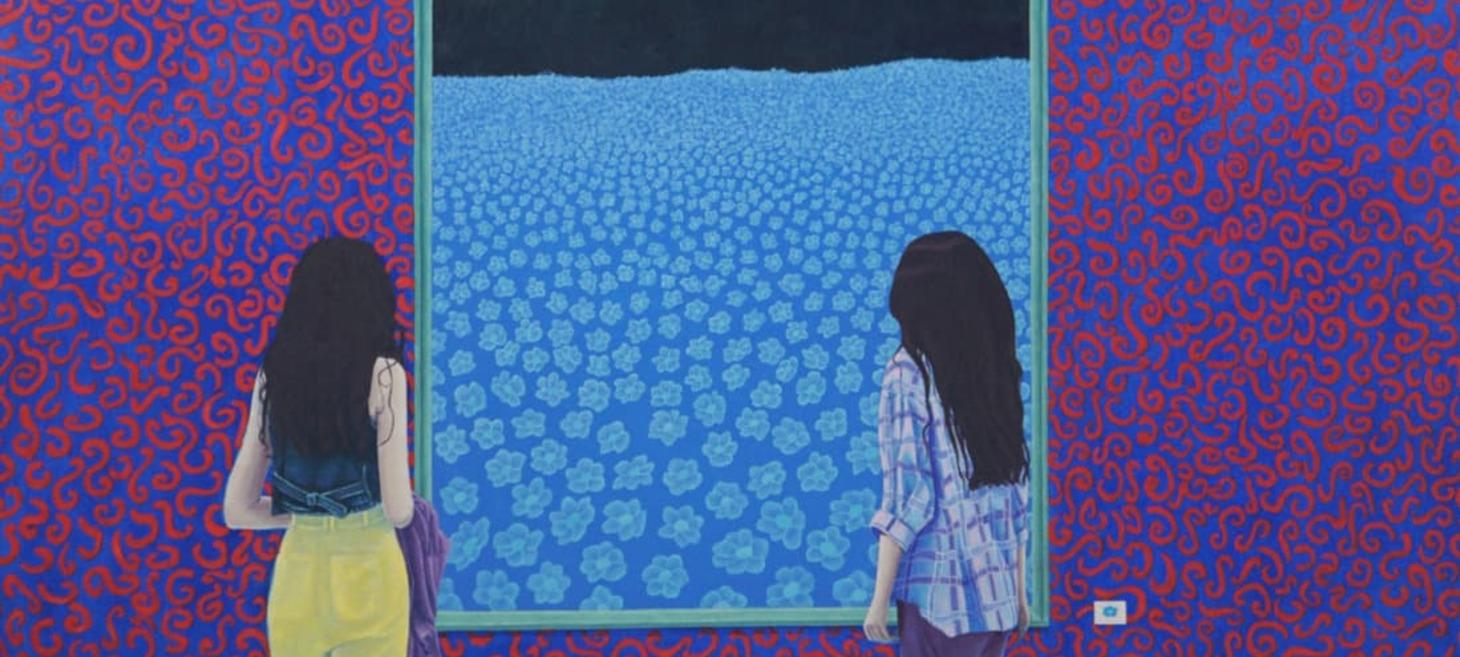

Can going to the museum actually improve your health? Daisy Fancourt, an epidemiologist at University College London, says yes—and she's got a decade of data to prove it. Her upcoming book, Art Cure: The Science of How the Arts Save Lives, draws on studies tracking tens of thousands of people over decades, linking regular cultural engagement to reduced depression, lower blood pressure, and better cognitive function. Maxwell Rabb reports for Artsy that one particularly compelling finding from King's College shows viewing original artwork reduces cortisol by 22%, compared to just 8% for reproductions.

Here's where I get skeptical, though. I love good news about art's health benefits—but this specific finding makes me question the methodology. My theory? The benefits might come from actually going out to a museum and experiencing the social and physical activity of that outing, not from some magical property of original art versus reproductions.

The King's College study followed 50 adults who viewed works by Manet, van Gogh, and Gauguin at The Courtauld Gallery, then compared their stress responses to viewing reproductions in a controlled environment. Yes, cortisol dropped more dramatically for the gallery group—but was that the art itself, or the act of leaving home, walking through museum spaces, and engaging in a cultural ritual?

Maybe we need a third control group: people who just go to museums and look at the architecture.

AI in Visual Arts

11 Famous Roy Lichtenstein Paintings That Define Pop Art

Art in Context's Isabella Meyer walks through eleven of Roy Lichtenstein's most defining paintings—from Whaam! to Drowning Girl—showing how he turned comic book panels and commercial graphics into museum-worthy art by scaling them up, flattening them with Ben-Day dots, and presenting them without apology. What was once considered "low" culture became fine art simply by being seen differently.

I keep thinking about how Pop Art was genuinely strange when it arrived. Lichtenstein took what the art world dismissed—comics, ads, mass-produced images—and by reframing them with intention, forced everyone to reconsider what could count as serious work. We're in a similar tension with AI right now. On one side there's what people call "AI slop": low-effort, high-volume images churned out from generic prompts, optimized for feeds rather than meaning.

On the other side is quieter but far more interesting territory, where artists fold AI into a broader practice—using models as sketch partners or generative darkrooms—while staying firmly in charge of the vision and emotional core.

Will there be a "Roy Lichtenstein of AI-supplemented art" who makes that difference impossible to ignore, legitimizing human-driven, AI-assisted practice without endorsing the flood of slop?

Artificial Intelligence and Creativity

AI That Turns Museums into Conversations: the Digital Twin

Museums have spent decades chasing "engagement"—building apps, touchscreens, audio tours—yet still treat every visitor the same way, with identical wall labels whether you're a scholar or a tourist. ArtsJournal's Douglas McLennan argues that museums mistook engagement for amplification, wrapping technology around art rather than rethinking the relationship between art and visitor.

What strikes me most is how digital culture moved from broadcast to dialogue years ago—comments instead of captions, meaning negotiated rather than delivered—while museums stayed frozen in one-way transmission mode. I've felt this gap personally. When my wife and I travel, we've started using Perplexity or custom AIs during museum visits, snapping photos of those minimal plaques and asking for deeper context.

That works remarkably well, often citing 70+ resources to create something like a personal tour. The fact that we're taking matters into our own hands says everything about the current state of museum interpretation.

McLennan proposes a "Digital Twin" of exhibitions—conversational AI built from a museum's own scholarship that listens and responds in real time, adapting to what each visitor actually wants to know. Could this finally bridge the gap between the curatorial tour experience and the generic wall label?

Design

A Quarter Century of Design: the 25 Biggest Creative Moments of the Last 25 Years

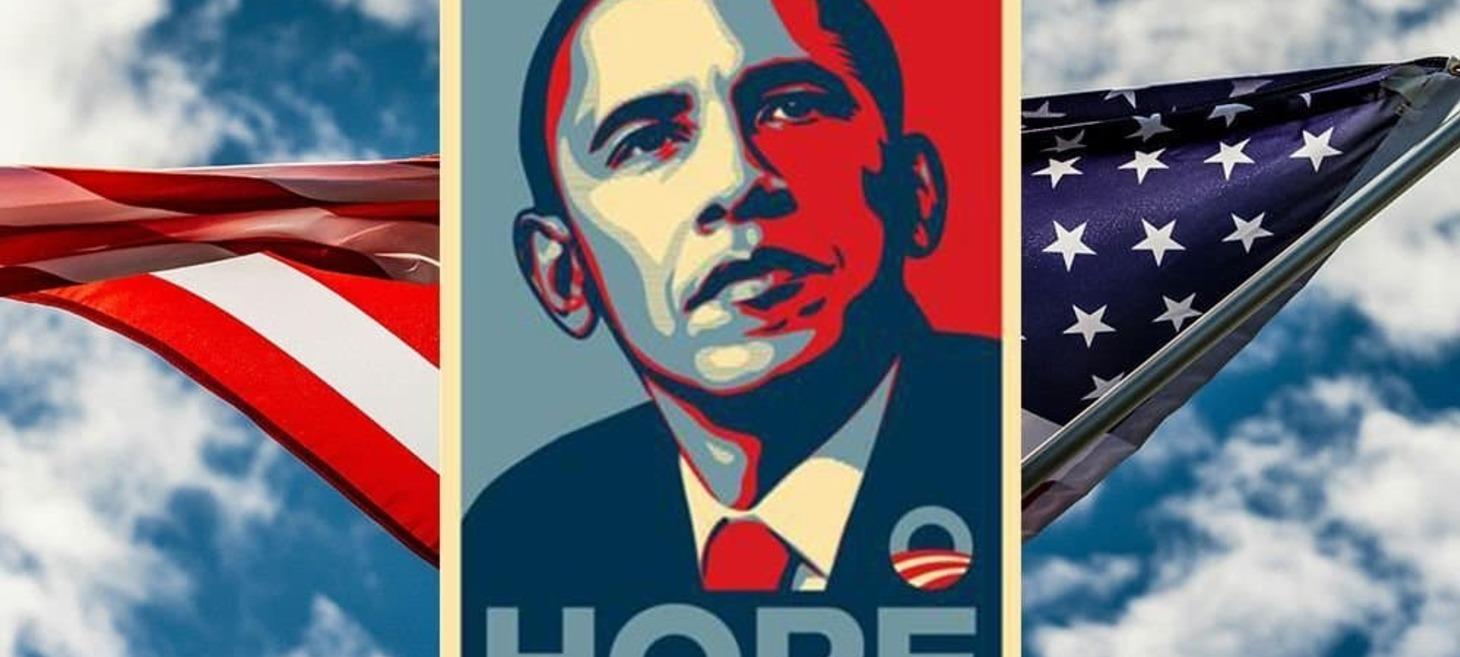

Looking back at 25 years of design decisions reveals how dramatically our visual world has shifted—from the iconic iPod silhouette to AI-generated imagery that's rewriting creative rules. Creative Bloq has assembled the design moments that didn't just capture attention; they fundamentally altered how we create, consume, and think about visual culture.

The list made me do a double-take at first. Apart from the nostalgia, this article made me go "wait, what?" But then each design trend totally made sense in its own way. Some choices seemed random or even questionable until you remember the context—the moment when that particular visual language broke through and suddenly everyone was speaking it.

What strikes me is how many of these "biggest moments" were initially controversial or misunderstood. The designs that change everything rarely feel safe when they first appear—they challenge our assumptions about what good design should look like.

Which design moment from the past quarter-century fundamentally changed how you approach your own creative work?

Sculpture

Reference Books Are Carved and Cut into Sculptures That Transform Knowledge into Art

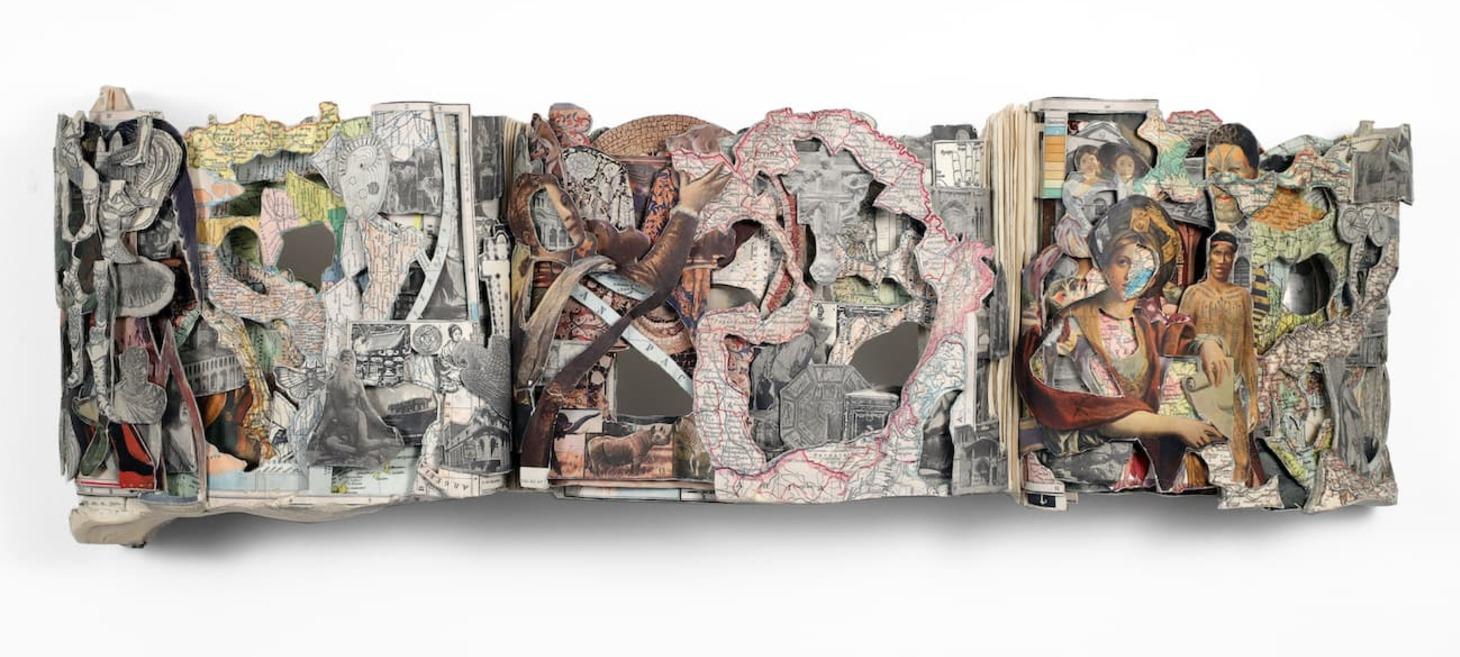

Atlanta-based artist Brian Dettmer transforms encyclopedias, atlases, and reference volumes into stunning sculptural forms by carefully carving away layers with surgical precision. As Sage Helene reports for My Modern Met, Dettmer doesn't add or rearrange anything—he simply removes material to expose the images, diagrams, and text already embedded within the pages. His current exhibition, In-Formation, runs through January 2026 at Riverside Arts Center in Illinois.

What I love about this work is the playful irony at its core. Books themselves are technology—just old technology that we've largely moved beyond. We forget that printed reference books once represented the cutting edge of information storage and retrieval. Now they're being transformed into art objects, their original function rendered obsolete by digital alternatives.

These carved volumes force us to reconsider what happens when one technology supersedes another. Instead of simply discarding outdated media, Dettmer reveals their hidden beauty by turning them inside out—literally exposing the layers of knowledge they contain.

What other obsolete technologies might deserve this kind of artistic resurrection?

Art and Politics

Norman Rockwell Was 'Antifa,' Says the Artist's Granddaughter

The Department of Homeland Security sparked a controversy this summer when it appropriated Norman Rockwell's paintings to promote what his family calls a "segregationist vision of America." Using images like Salute the Flag—showing only white Americans gazing at Old Glory—alongside Coolidge quotes about protecting the homeland, DHS recast the beloved illustrator as a culture war champion. Alex Greenberger reports for ARTnews that Rockwell's granddaughter, Daisy, fired back with a bold declaration: "Norman Rockwell was antifa."

I find it fascinating how one person's patriot becomes another person's terrorist. The idea that Norman Rockwell—painter of Saturday Evening Post covers and small-town nostalgia—could be branded as either would have seemed absurd just years ago. Yet here we are, with both sides claiming him.

The reality sits somewhere in that uncomfortable middle ground. Rockwell himself said he was "continuously trying to eradicate" prejudices he was born with, and he did decline to paint recruitment posters for the Vietnam War. But was he antifa? Was he anti-fascist? The labels feel too neat for someone who spent a career painting nuance.

Which version of America are we actually fighting over—his, ours, or the one we imagine existed?

The Last Word

The Last Word

Thanks for spending time with this week's stories. I'm genuinely curious whether you think measuring art's health benefits or designing AI museum companions brings us closer to understanding what art does for us—or just gives us comfortable numbers to cite. Either way, I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Best, Juergen