Greetings from Juergen

Greetings from Juergen

Hi all,

This week's newsletter turned into something of an accidental Halloween edition, and I'm not mad about it. We've got Guillermo del Toro comparing Frankenstein's creator to a careless tech bro while declaring he'd rather die than use generative AI—a characteristically blunt take from a director who's never shied away from monsters, whether they're on screen or in Silicon Valley. Then there's Scott Power's annual Art World Horror Stories podcast episode featuring tales that'll make you shudder: racist comments flooding an artist's social media, Hurricane Helene destroying Asheville's entire River Arts District and displacing 700 artists, and a jealous wife literally slicing up her husband's lover's painting. If that's not enough spooky content, we also have a journalist who recreated Walt Disney's 1929 The Skeleton Dance using motion capture dots during a back pain research study.

Beyond the seasonal scares, we're looking at some genuinely thought-provoking work. There's Elise Swopes' Chasing Waterfalls series—Chicago skyscrapers swallowed by cascading water, created through painstaking manual composites years before AI could do it in seconds. Photo Oxford returns with Michael Christopher Brown using AI not to generate pretty pictures, but to protect the identities of vulnerable Cuban workers he photographed. And 17 Indigenous artists staged an unauthorized AR exhibition at the Met, digitally transforming 19th-century colonial paintings with powwow dancers and pointed inversions that ask who gets to tell American stories. We've also got the world's smallest pixels hitting the theoretical limit of human vision, and yet another absurd AI gadget that solves problems nobody asked to have solved.

Film & Video

Guillermo Del Toro Compares Frankenstein to a Careless "Tech Bro," Says He Would "Rather Die" Than Use Generative AI

Guillermo del Toro has never been one to mince words, and his latest comments about AI in filmmaking are characteristically blunt. Speaking to GamesRadar, the visionary director behind Pan's Labyrinth and The Shape of Water compared Frankenstein to a careless "tech bro" and declared he would "rather die" than use generative AI. His pithy summary? "My concern is not artificial intelligence, but natural stupidity."

I love del Toro's work and his attitude, but I think AI will become so prevalent in the film industry's back-end video editing processes and automations that it will become increasingly hard to avoid it. There's a useful distinction we need to make here between generative video and AI-powered editing tools.

If he's saying he'd rather die than use generative video, that's one thing—and I respect that line. But if he's saying he'd rather die than use any AI-powered filmmaking tools, that will be hard to achieve.

Where do you draw the line between tools that support your creative vision and tools that replace it?

Photography

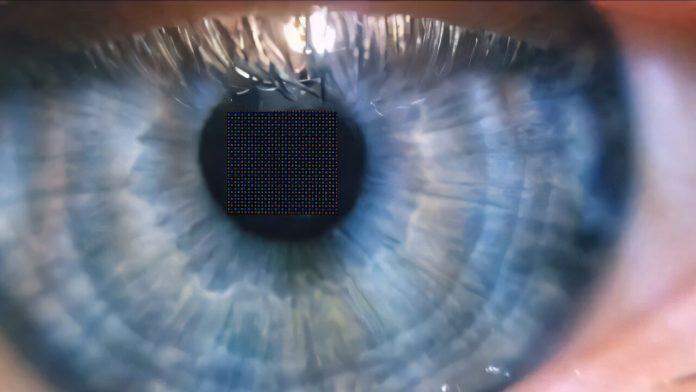

World's Smallest Pixels Achieve the Sharpest Display Ever Seen by the Human Eye

Swedish researchers have built a display with pixels so tiny—560 nanometers—that they've hit the theoretical limit of human visual perception. The team from Chalmers University, the University of Gothenburg, and Uppsala University created "retina E-paper" that packs 25,000 pixels per inch into a screen the size of a human pupil, as reported by Knowridge Science Report. They even recreated Klimt's The Kiss on a surface smaller than a grain of rice.

Here's what strikes me about this achievement: we've spent two to three decades obsessing over resolution, pushing it far beyond what our eyes can actually detect. And now we've finally arrived at "enough." Meanwhile, photographers—myself included—take these pixel-perfect images and run them through Instagram filters to add back the grain that analog photography had naturally. We emulate Fuji, Aqua, and Kodak grain structures, retrograding our perfect captures to introduce the imperfections we supposedly evolved past.

There's something wonderfully absurd about building displays that exceed human perception, then using them to mimic the grainy, emulsion-driven aesthetic of black and white film that shaped photography for generations.

Have we been chasing technical perfection just so we could choose imperfection on our own terms?

Facets of Truth as Photo Oxford Opens

Photo Oxford returns this month with a theme that cuts right to the heart of our current moment: Truth. Running through mid-November, the biennial festival explores how photography both reveals and obscures reality—from apartheid-era confessions to AI-manipulated employability scores. Writing in 1854 Photography, Rachel Segal Hamilton spotlights new director Katy Barron's vision for exhibitions that embrace complexity rather than easy answers.

What drew me in was Michael Christopher Brown's 90 Miles series. He photographed Cubans traveling between their home country and Florida for work, but faced a crucial problem: how do you tell their stories without putting them at risk? His solution fascinates me—combining traditional documentary photography with generative AI to protect their identities. It's not about replacing the camera with algorithms; it's about using both tools thoughtfully to make journalism possible where it otherwise couldn't exist.

This is exactly the kind of AI application that interests me—not generating pretty pictures from text prompts, but solving real ethical problems that documentary photographers face in the field.

Should protecting vulnerable subjects become AI's most defensible use case in photography?

Artificial Intelligence and Creativity

An AI Camera for Your Iphone: Caira Tries, but Do We Need It?

Caira wants to solve a problem that doesn't exist. This new iPhone attachment combines physical lenses with Google's Nano Banana AI model to instantly transform your photos—turn water into wine, alter someone's hair, fabricate memories that never happened. The startup Camera Intelligence plans to launch it November 4th, but as Domus rightly asks in their critical assessment: why would anyone need a dedicated device for something your phone already does?

The pace of nonsensical AI product launches has reached absurd levels. I loved this line from the article: "I wish I had a camera that could alter reality in front of my very eyes, faster than I could do that by uploading my picture to ChatGPT," said no one ever. Yet here we are, watching inventors respond to pleas that were never made.

This is textbook solution-in-search-of-a-problem thinking—startuppers building hardware for AI features that work perfectly fine as software, creating friction where none needed to exist.

Will Caira join the AI Pin in the graveyard of overhyped gadgets that mistook current AI trends for actual consumer needs?

Definitely Not AI

Chasing Waterfalls Showcases Stunning Surrealism

Elise Swopes' Chasing Waterfalls series presents Chicago's skyline swallowed by cascading water—massive torrents pouring over skyscrapers in images that feel both beautiful and ominous. Moss and Fog recently revisited these several-year-old composites, noting how they've gained new resonance in our era of climate anxiety and rising seas. The reference to Spielberg's AI and its half-submerged future cities only sharpens that edge.

What strikes me most is that Swopes created these without AI, through painstaking manual composite work. Now that generative AI can produce similar surreal imagery in seconds, I find myself wondering: does that ease of creation diminish the vision and message embedded in work like this? Does the democratization of image-making through AI dilute artistic potential, or does the intentionality behind the creation still matter more than the method?

The technical accomplishment becomes part of the meaning—knowing someone spent hours perfecting each waterfall's flow and light interaction adds weight to the environmental metaphor these images carry.

When the barrier to creating surreal visions drops to near-zero, does that change how we value the vision itself?

Q+ART & Podcast Interviews

Art World Horror Stories: From Natural Disasters to Mangled Masterpieces and Social Media Meltdowns

Melissa Diggs watched racist comments pile up under her print that simply read "racism is wrong." Wendy Newman salvaged umbrellas from the Marquis Art Gallery after Hurricane Helene destroyed Asheville's River Arts District, displacing 700 artists. Jacobina Oele discovered her painting had been sliced up by a jealous wife. Scott "Sourdough" Power at Not Real Art narrates these three chilling tales in his annual Art World Horror Stories podcast episode—and yes, the timing is fitting.

I'm not necessarily trying to make this a Halloween edition of our newsletter, but it is that time of the year. My good friend Scott Power has once again featured Art World Horror Stories in an annual episode of his podcast. Plus we did have a Frankenstein story in this issue as well.

These stories remind me that the art world's real horrors aren't supernatural—they're the very human threats of censorship, natural disaster, and jealousy that can destroy creative work in an instant.

What horror story might you be living through right now without even realizing it?

Dance

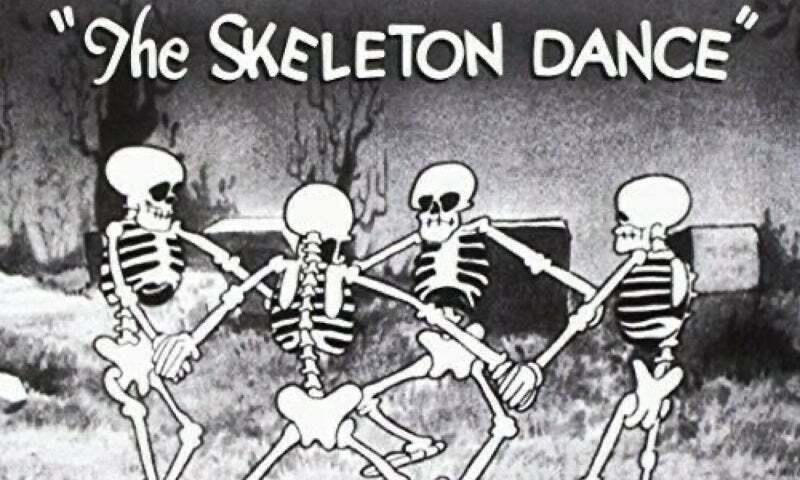

Watch My Skeleton Dance for Science

When Bob Grant, deputy editor at Nautilus, showed up to a Washington University research lab for a back pain study, he became an unwitting performer in the best possible way. Covered in motion capture dots and stripped down to compression shorts, he was supposed to bend and stretch so researchers could study movement patterns in people with chronic pain. Instead, Grant saw an opportunity too perfect to resist—he recreated Walt Disney's 1929 The Skeleton Dance, turning clinical data collection into spooky seasonal art.

Here's another Halloween-themed piece of art news, this time about dance. We don't feature enough of it, but this seasonal skeleton dance is for a good cause—solving back pain, which affects 60-80 percent of adults at some point in their lives.

The research itself is fascinating: by following participants over a year and digitizing their movements, physical therapist Linda Van Dillen's team hopes to identify the precise moments when acute pain transitions to chronic suffering. Early detection could transform treatment before temporary discomfort becomes a lasting condition.

What better reminder that creativity can emerge anywhere, even in the most clinical settings?

The Last Word

The Last Word

Thanks for spending some time with these stories this week. Whether you're celebrating Halloween or just navigating the everyday horrors and wonders of the art-tech landscape, I'd love to hear what resonated with you—or what you think I'm getting wrong. The conversation is always better when it's two-way.

Best, Juergen