Greetings from Juergen

Greetings from Juergen

Hi all,

This week I found myself thinking about the music tools I used to love—the samplers, digital workstations, and generation software that once felt revolutionary. After decades of dabbling at the cutting edge of digital music, I'm back to playing acoustic guitar, finding more connection in wood and strings than in algorithms. That shift mirrors a bigger story emerging across creative fields, and several articles this week helped me understand why. We're looking at tradition versus technology in music composition, Spotify's new "responsible AI" partnerships with major labels, and what happens when economic incentives collide with artistic values.

Beyond music, this week explores how photography—once our most trusted link to reality—continues its algorithmic transformation, from Paris Photo's Digital Sector to Milan's "Transizioni" exhibition. We also examine how New Zealand's "biculturalism" reveals patterns in how we talk about culture while avoiding economic history, why visual artists are demanding retrospective payments for AI training data, and whether we can actually define "slop" in any meaningful way. Each story asks variations on the same question: how do we preserve human choice and creative intention when technology makes generation easier than creation?

Societal Impact of Art and Tech

"Culture Talk" and Indigenous Economic History

Miranda Johnson's sharp essay in the Journal of the History of Ideas examines how New Zealand's "biculturalism"—the idea that Māori and Pākehā cultures form equal pillars of national identity—obscures a more complex economic story. While progressive discourse celebrates cultural recognition and frames Indigenous Māori as victims of colonial dispossession, it conveniently ignores how Māori leaders have actively pursued economic development for over a century. Today, the "Māori economy" is booming, with tribal holdings managing billions in assets.

Johnson's observation that "cultural explanations of political outcomes tend to avoid history" resonates far beyond New Zealand. I find it so helpful to read about this in other cultures because it serves to disconnect oneself from political preconceptions. The same patterns emerge in our own brief history—Black and white, North and South, old immigration versus new. Reading about biculturalism in another context lets us see the dysfunction more clearly.

What strikes me most is how progressive "culture talk" can actually perpetuate the very problem it claims to solve. By treating Indigenous culture as existing outside capitalism's history, we can't explain contemporary Māori economic success—leaving that narrative to the political right.

Can we acknowledge both historical injustice and present-day economic dynamism without one erasing the other?

AI in Visual Arts

Artists Should Receive Retrospective Payments for Works Used to Train Ai, Arts Organisations Say

A coalition representing more than 100,000 visual artists has issued a bold demand: AI companies should make retrospective payments for the copyrighted works they scraped without permission to train their models. As Joe Ware reports for The Art Newspaper, groups including the Design and Artists Copyright Society and the Association of Photographers want transparent disclosure of training datasets, fair licensing agreements, and compensation for what they see as theft. Derek Brazell from the Association of Illustrators points to websites like Have I Been Trained?, which has identified "billions" of images used without consent.

I find the framing fascinating—it really does echo current conversations about reparations for historical injustices. The AI industry has already appropriated copyrighted materials, and now artists want redress for that appropriation. I'm deeply sympathetic to these demands, but I'm also realistic about the outcomes. History shows us how difficult it is to unwind such situations once they've happened.

The comparison to the Luddites keeps coming to mind. I'm not saying artists are Luddites—far from it—but the arguments against the industrial revolution were similar: jobs disappearing, livelihoods threatened, traditional skills devalued. Those protests didn't stop the machines.

These days, "the art of the possible" means dealing with new realities on so many dimensions—are we prepared for what that actually looks like?

Photography

Paris Photo 2025: Innovative Curation

Paris Photo returns this November for its 28th edition, bringing 220 exhibitors from 33 countries to the Grand Palais. What makes this year particularly noteworthy is the fair's Digital Sector, where artists like Kevin Abosch are presenting AI-generated work trained on their own photographs—arguing this isn't a break from traditional photography but part of its evolution. Emma Jacob's piece in Aesthetica Magazine captures how the event has become a crucial conversation space about where photography is headed.

Being an ex-photography professional myself, I find these continuous developments fascinating. Photography once represented reality—I'm using the past tense intentionally here—but that reality has been augmented and faded since the advent of the digital camera. What draws me back to this medium, more than others experiencing similar algorithmic shifts, is photography's historically close tie to what we think of as real.

Even the smallest built-in algorithms—improving exposure, ensuring noiseless digital media, removing objects or artifacts, artificially increasing resolution—are what some call a "slippery slope." Unlike other art forms, photography's link to reality is what drives photojournalism's search for an increasingly elusive "truth."

How do we define authenticity in a medium that's been quietly algorithmic for years?

An Exhibition Explores How Ai Is Transforming Photography

Milan's Viasaterna gallery is hosting an exhibition that asks a question many of us are dancing around: what does photography even mean anymore? "Transizioni" brings together nine contemporary artists who merge traditional photography with sculpture, painting, illusionism, and generative AI, creating what curator Mauro Zanchi calls "hybrid images." Domus covers how these works challenge everything from archaeological restoration to the very act of pressing a shutter.

I love the idea of artists experimenting across mediums this way. It reminds me that controversy isn't new here—once upon a time, using photographic elements in painting or beaming a slide projector onto your canvas was considered cheating. Now that same creative friction comes from combining AI-generated imagery with traditional photographic methods. The tools change, but the spirit of experimentation stays constant.

What strikes me about this show is how it positions AI not as photography's replacement, but as another ingredient in the mix—like those slide projectors that once seemed so radical.

Maybe the real transformation isn't what we photograph, but how we define what counts as a photograph at all?

Artificial Intelligence and Creativity

Defining Slop

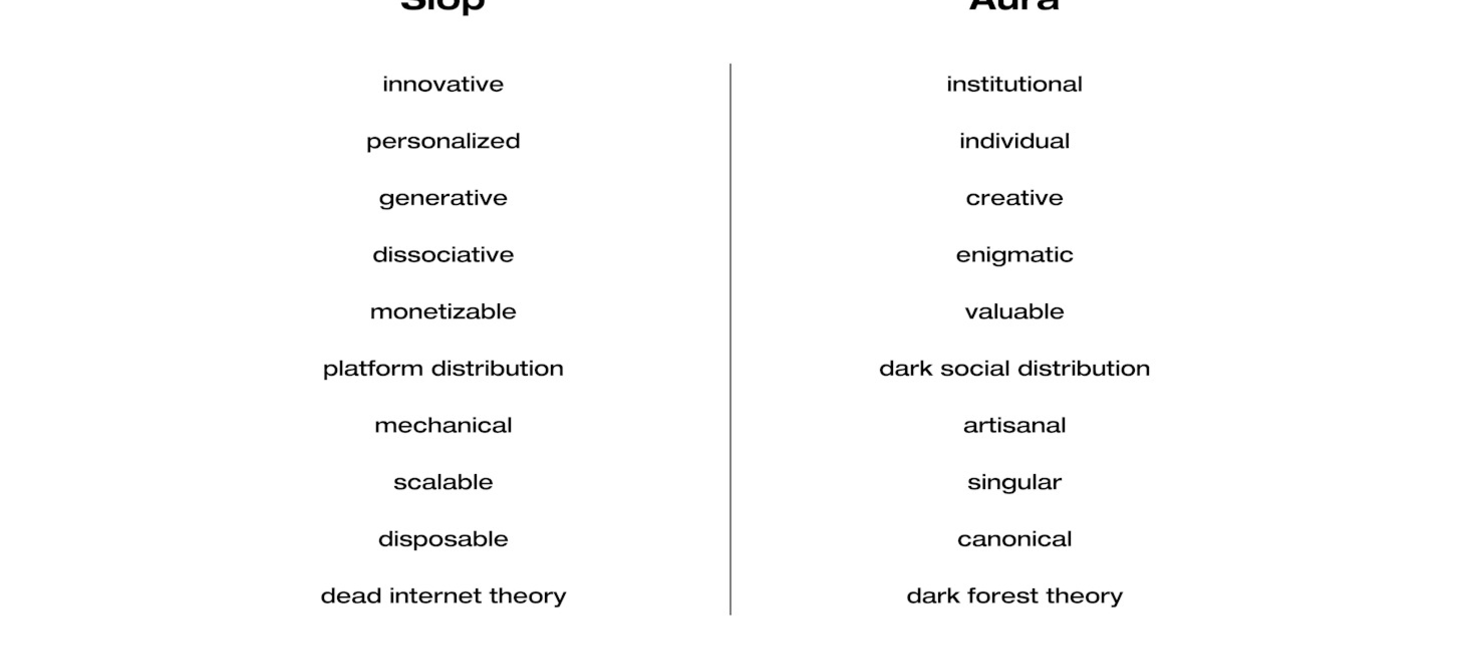

We love our binaries—good art versus bad art, human versus machine, authentic versus fake. But Sean Monahan's piece at 8ball.report challenges us to think harder about "slop," that catch-all term we've been using to dismiss AI-generated content. He argues that slop is simply whatever media format feels most dynamic and innovative right now, and that even Silicon Valley understands institutional approval matters—hence OpenAI's Sora screening at a Los Angeles theater, angling for that first Oscar-worthy film.

I keep asking myself: how do we actually define slop? Maybe, like most things worth examining, there isn't a black and white answer. We're living in the nuance of slop—that uncomfortable space where some AI-generated work feels hollow while other pieces demonstrate genuine creative intention.

Monahan writes that institutions allocate aura, and he's right. But what interests me more is his distinction between the generative and the creative: "The creative act is choice." AI can't choose, only react. So perhaps the question isn't whether we used AI, but whether human choice shaped the result.

Can we build a framework for discerning creative choice within AI-assisted work, or will we keep defaulting to simple dismissal?

The Last Word

The Last Word

Thanks for reading and thinking through these questions with me. I'm always curious to hear how these shifts are affecting your own creative work—whether you're gravitating toward older methods or finding new ways to make technology serve your vision. Your perspectives help me see these changes from angles I might miss on my own.

Best, Juergen