Greetings from Juergen

Greetings from Juergen

Hi all,

This week's stories: where's the line between using AI as a tool and handing over the work entirely? Bandcamp just became the first major music platform to ban AI-generated content outright, which I find refreshing—but it raises tricky questions about what counts as "AI content" when even dust removal in Lightroom can trigger false flags. Meanwhile, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna used AI to reconstruct missing portions of a 17th-century painting through an iterative process between technology and art historians, showing what genuine collaboration can look like when humans stay in charge of the decisions.

That theme runs through almost everything here. Art authentication experts are pushing back against AI tools that claim to make objective determinations about Old Masters, insisting these systems should augment connoisseurship rather than replace it. Apple's research into multi-spectral cameras has me thinking about how far computational photography can push before we stop calling it photography at all—especially when invisible light gets processed by AI before we ever see the image. Even the story about a student eating AI art in protest feels like it's wrestling with the same anxiety about what gets replaced versus what gets preserved. How long can creative fields maintain this "assistive only" stance before economic and institutional pressures push toward full delegation?

AI in Visual Arts

The Triumph of Bacchus

When the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna wanted to see what Michaelina Wautier's "The Triumph of Bacchus" looked like before it was cropped in 1763, they turned to AI. Working with the Ars Electronica Futurelab, art historians used high-resolution gigapixel images and machine learning to reconstruct the missing 40 centimeters—recreating portions of figures lost for over 260 years.

What strikes me here is the restoration by consensus. The more art history experts you involve, the more accurate the reconstruction becomes, but I'm always uneasy about actually making changes to the original work. That's why I appreciate that a new version exists parallel to the original—visitors can explore both at the museum on a touchscreen.

The focus was on an iterative process between technology and art history expertise: the Futurelab developed numerous variants for the missing parts of the painting based on textual and visual specifications provided by the experts. The results were jointly reviewed and adjusted until a version was created that matched Wautier's work in terms of style, content, and history.

In this age of digital reconstruction, should we prefer screen-based restorations that preserve the original intact, or does physical restoration still have its place?

Photography

Apple Explores Multi-Spectral Cameras to Power Smarter Iphones

Apple is reportedly researching multi-spectral camera technology for future iPhones—a shift that would let the device capture data beyond visible light. According to TUAW, this isn't coming soon, but it represents a fascinating evolution in how consumer cameras might work. Instead of just recording red, green, and blue light, these cameras would analyze a wider electromagnetic spectrum to improve depth detection, subject separation, and environmental understanding.

I hadn't really thought about what it means when cameras use invisible light to interpret scenes before AI processing translates everything back into visible images for us. Whether it's enhanced depth perception, depth of field control, or even infrared-style effects, the applications stretch beyond everyday photography into scientific imaging and other specialized fields.

The thing is, AI processing on camera chips is already here—every digital camera now does some automated processing. Film systems were always limited to available light, but we've moved past that constraint entirely.

How much further can computational photography push before we stop calling it photography at all?

Artificial Intelligence and Creativity

NFT Paris and RWA Paris Canceled with One-Month Notice Due to 'Crypto and NFT Market Collapse,' Founder Says

Europe's largest NFT conference just pulled the plug, and the timing says everything about where we are right now. NFT Paris—along with its sister event RWA Paris—canceled with just one month's notice, citing what founder Alexandre Tsydenkov called a "market collapse" that made the events financially impossible, reports George Nelson in ARTnews. NFT sales have plummeted from $4 billion to around $800 million, and about 96 percent of NFT collections are now considered dead.

I'm not convinced this is simply about NFTs dying. What I'm seeing might be more about the broader pushback against AI, web3, and what gets dismissed as "AI slop." We're watching a polarization happen—organic, authentic, human-centered work on one side, and everything crypto, algorithmic, and AI-associated on the other. The question that keeps nagging me: are we being too reactive here? Are we filtering these developments with enough nuance to understand what has genuine potential versus what deserves to be left behind?

The pendulum swings back and forth, and right now it's moving hard against all things digital and algorithmic. I'd love to see something like a Gartner hype cycle applied to consumer attitudes toward AI—though I suspect the typical model won't be enough to explain what's happening in the age of AI.

My expectation? It'll take another year to sort out what actually matters from what was always just noise.

How Art Welcomes 2026: Unbearable Weight of Keeping Meaning

What happens when art stops running? Dilek Yalçın's essay in Daily Sabah captures something I've been feeling but hadn't named—a subtle shift happening beneath 2026's unremarkable arrival. Artists are sensing a change in weight, a reordering of priorities as AI becomes ordinary and the question shifts from what art can do to what it should hold.

The passage that stopped me cold describes how contemporary art has been sprinting for over a decade. Speed became habit, visibility a reflex. To produce was to exist; to pause was to risk being forgotten. That exhaustion we've been carrying individually? It's become structural. We've normalized something unsustainable, and 2026 might be the year we finally acknowledge it.

Yalçın argues that when machines can generate endlessly, the most radical artistic act becomes the decision to mean something specific—to care, to take responsibility for form and consequence. The physical returns with renewed urgency because texture, imperfection, and gestures that cannot be undone begin to matter structurally, not sentimentally.

Can we build spaces for art that don't demand constant performance, where silence functions as material again?

Definitely Not AI

Student Arrested After Eating AI Art and 'Ruining' Display

A student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks was arrested for eating AI art. Yes, you read that right—eating it. Graham Granger ripped 57 out of 160 images off gallery walls and consumed them in what he called a protest against AI-generated work, according to Connor Bennett at Dexerto. The artist, Nick Dwyer, had created the exhibition to explore his experience with "AI psychosis," making this act of destruction both ironic and troubling.

I honestly can't decide where this story belongs. Should it be filed under "definitely not AI," or is the protest itself the actual artwork here? There's something meta about it—almost collaborative in a strange way. It reminds me of that banana taped to a wall that sold for six million euros at Art Basel in Miami.

Even some Reddit commenters wondered if the damage was "secretly the art piece," though Dwyer quickly shut that down. He's pressing charges, pointing out the personal nature of the work and the labor involved in hand-cutting and hanging each piece.

Where exactly does performance art end and criminal mischief begin?

Exhibitions & Events

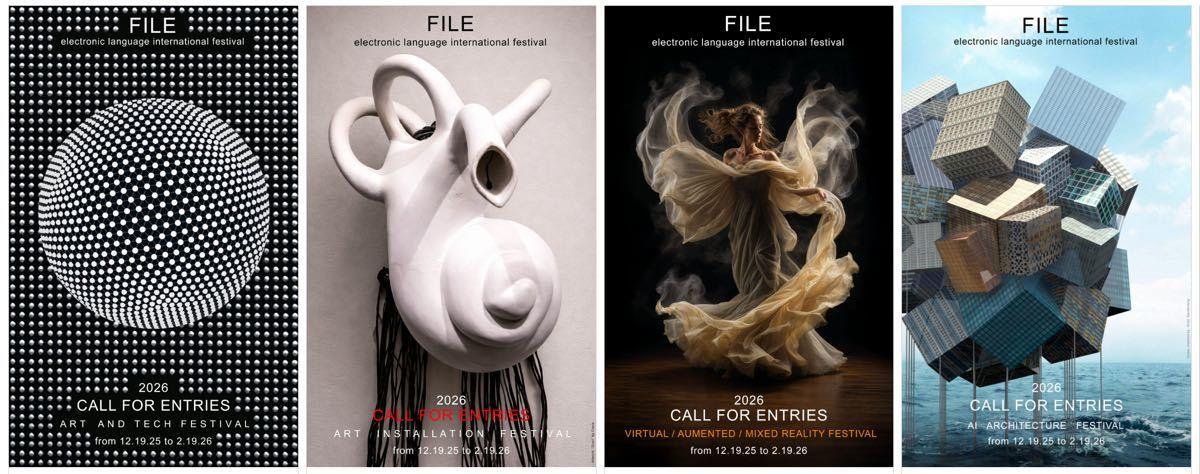

FILE 2026 - Call for Entries - Art and Technology Festival

Brazil's FILE—the Electronic Language International Festival—just opened its call for entries ahead of its 26th edition running August through October 2026 in São Paulo. The festival, detailed on I Send You This, welcomes artists, researchers, and educators to submit work exploring what they call "contemporary technological poetics," where interfaces, data, space, and body converge.

That phrase caught my attention. Art and tech festivals aren't exactly common, and I'm genuinely curious what "contemporary technological poetics" actually means in practice. The "Electronic Language" branding suggests a specific focus on communication and expression, yet the festival promotes itself as a broad art-and-technology intersection. I'd love to see a clearer definition that bridges those concepts.

FILE seeks projects that "propose new forms of perception, interaction, and critical and poetic reflection," which sounds ambitious but leaves me wondering how they evaluate what qualifies as sufficiently new or critical—and whether innovation in language systems gets priority over other tech-art approaches.

If you're working at this intersection and have until February 19 to apply, what does your version of technological poetics look like?

Digital Archiving and Art Preservation

In the Age of AI, Can Art Expertise Be Digitised?

The art world is facing a peculiar dilemma: AI tools are making bold authentication claims about Old Masters, declaring previously dismissed copies to be authentic Caravaggios and Rubenses—often over the objections of leading human experts. Jane Kallir, an authority on Egon Schiele who runs the Kallir Research Institute, pushes back hard in The Art Newspaper, arguing that AI's promise of objectivity misses what authentication actually requires.

We've covered art authentication before in this newsletter and explored AI as an assistive technology in this space. I think this article dispels any notion that these tools might ever be more than that. There's a temptation to let AI be the final "objective determinator" of authenticating artworks, just as we see in other fields. But leaving it up to AI isn't necessarily wise.

Using AI as a tool to augment human capacities is one thing; letting it determine authenticity independently is quite another—and I don't think that's really being proposed. AI tools for authentication will continue to be useful to experts who know how to wield them without surrendering the decision-making entirely.

Where do you draw the line between assistance and abdication?